This article is Part 3 in a 4-Part Series.

- Part 1 - Refactoring to Data Driven Tests

- Part 2 - How to get data for Data-Driven Tests?

- Part 3 - This Article

- Part 4 - Tips, tricks, and good practices for Data-Driven Testing. Part 2.

As promised here and here, this will be tips, tricks, and good practices for data-driven tests.

If You want to know more about data-driven testing see my previous posts on this topic.

Here we go.

Before we begin

I will be converting this series into an ebook, or something like that, with additional source code and examples. If You want to get it please subscribe:

Keep data in files.

I showed this in the previous post, but it is the most important tip. Save test case data as files and use the TestCaseDataAttribute to declare the function that will read it and pass as test cases. Something like this:

public static TestCaseData[] GetData()

{

var retArray = Directory.GetDirectories("MyTestDataFolder", "*", SearchOption.AllDirectories)

.OrderBy(a => a)

.Select(a =>

{

var ret = new TestCaseData(JsonConvert.DeserializeObject("testdata.json"));

ret.ExpectedResult = JsonConvert.DeserializeObject("expectedResult.json");

return ret;

})

.ToArray();

return retArray;

}

Now to te next most important area: folder structure.

Tips on folder structure in Data-Driven Tests:

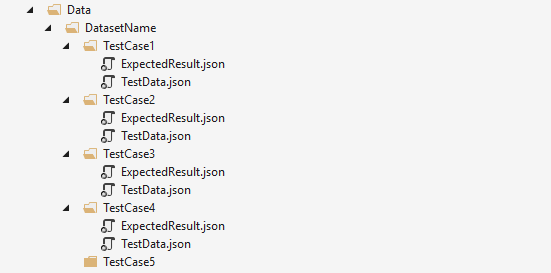

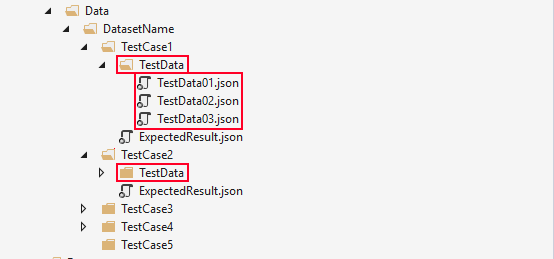

Since our test data is stored in files and folders, organizing them is important. Below is a sample structure I use to store test data files:

Doesn’t look sophisticated, and isn’t once it is ready. But there are some tips there:

1. Have one Data folder in the test project.

Having one central Data folder sounds like an anti-pattern. Let me explain why it isn’t in data-driven tests:

- They are easier to locate. To read the test files, we need to know the relative path to them. One that starts at the project root. This means that if we place the test data files deep in the folder structure of the test project, we will need to duplicate that path in the test data path. Making the test more fragile for simple name changes.

- Data reuse. Reusing test objects in multiple tests is, in most cases, an anti-pattern. It leads to many people modifying a single object, or a class creating a no man’s land. A part of the test project that isn’t owned by any particular test or a person. In data-driven test data is taken from real-life usage of the system. It isn’t made up, but something that happened. There is no point in modifying it (except for upgrading the object structure). We mostly create a new verification data set.

2. Second level folders - the name of the dataset

This is the folder over which we iterate in the data reading method. The most apparent naming convention is to name it after the test. Sounds reasonable, but leads to one of the anti-patterns in data-driven testing: many test folders, each with a few tests and every test folder with a different file format. How to do it better? I propose naming the test after the dataset that it is.

For example: In cookit.pl, I am parsing HTML websites and extracting recipe text and ingredients. The main logic is in the

Parsemethod in theRecipeParserclass. I initially named the folderRecipeParser_ParseWebsites. When I renamed it toHtmlRecipePagesit opened the possibility to use the HTML websites for testing:

- HTML validation

- encoding detection

- recipe text detection

- ingredient detection

- etc.

Names matter. Use good ones.

3. Third level folders represent the data cases

This level is the easiest to explain. Each bug, test case has its folder. It should also have a name representing the problem that it tests.

4. Don’t be afraid to add additional grouping folders

I don’t like to have many folders in the solution tree, so I group them. If this is also your preference, remember that the grouping key should be simple and easy to understand. Some that I used:

- a website domain name

- name of the client that encountered the error

- application version

Anything will do as long as it is simple to explain and intuitive.

File tips

1. Use proper file types.

JSON is the go-to format because of readability, and ease of import/export. Some rules make working with them easier:

- Consistent formatting. As we said, most of our data files will come from system usage. Those files should not be saved with formatting (it is a nontrivial overhead). The formatting should be applied when such file is used in tests. Define a convention, or better yet a tool that will do the formatting. It is good to have them for data files for the same reason why we have them for code files - people will argue over them. I, personally, use the VS Code for formatting.

- Consistent encoding. A very similar problem as the one above. It is obvious to use the same encoding for one dataset, but we need to have the same for ALL data files.

- Not only JSON. Some data types are just perfect for tabular files formats like CSV, TSV, etc. For reading them, I recommend CsvHelper

- Remove not important fields. We don’t always have a perfectly logged object. When using a data file from production, analyze the properties, and remove the unnecessary ones. Remember, tests should be optimized for readability. This also applies to test data.

- Anonymize the data. Don’t commit to the repo data files that contain sensitive or personal data. Once you identify the problem anonymize the data file.

JSON tips

- 1 object in one file. Some tests will take in a collection of elements. Then it is tempting to have one JSON file with an array of objects. Don’t do it. JSON files aren’t easy to merge. Having big files is just asking for trouble. How to deal with this? I introduce a fourth level folder and save each object as a separate file:

- Consistent formatting. I know I am repeating myself, but this is important. Have consistent formatting

CSV/TSV tips

- Don’t use a comma as the separator. Commas are used in numbers, texts and aren’t too visible when opening the file. What to use, then? I use a tab.

- Set the culture explicitly for reading the file. Culture on your machine may be different than the one on the build agent machine, or other developers. Set the culture explicitly and save yourself a lot of debugging. A sample using

CsvHelperNuGet package:

var csvReader = new CsvReader(reader)

{

Configuration =

{

CultureInfo = CultureInfo.CreateSpecificCulture("en-US")

}

};

2. How to handle large files in data-driven tests

Large files or a large number of files can be a problem because they will significantly increase the repo size making Git slower. Here we have two equally good solutions:

2.1. Use Git LFS (Git Large File Storage)

Git LFS was designed to store nontext or large files. Files stored using Git LFS are visible ass regular files in the repository, but changes to them aren’t tracked using the standard git diff mechanism. When cloning the repository with Git LFS, we will only get the latest version of the file, saving us a lot of disk space. Sound awesome. And for most cases it is. But it has some drawbacks:

- Requires support on the git server. Git server has to support Git LFS. Most online providers do, but some older on-premise solutions might not.

- Requires an extension on every developer machine. Each developer has to install Git LFS. Without the extension, we will see text pointers to Git LFS files.

2.2. Use Git submodules

Git LFS is fantastic, but for text files, we might still prefer the usual git way. What then? The answer is to use Git, but put the files in a separate repository that will only contain data files. Then add that repository to the code repository using a submodule:

git submodule add GIT_REPOSITORY_URL

This call will clone the data repository to a folder inside our standard repository.

When cloning the code repository, we only need to add one flag to the clone call (--recurse-submodules):

git clone --recurse-submodules

This approach has some significant benefits:

- Easy to share. Because it is a separate repository, it can be used as a normal repository or used as a submodule in other repositories.

- Separate versioning. The code repository links to the specific commit in the data repository. Versioning them separately can be handy when we are getting test case data from an external source and may not be in control of the structure.

This is not the end.

Jekyll doesn’t like long posts (I learned it the hard way with this one), and I also feel this is a good moment to break this post. To be continued …