This article is Part 1 in a 4-Part Series.

- Part 1 - This Article

- Part 2 - How to get data for Data-Driven Tests?

- Part 3 - Tips, tricks, and good practices for Data-Driven Testing. Part 1.

- Part 4 - Tips, tricks, and good practices for Data-Driven Testing. Part 2.

I am not a big fan of writing tests. I like having them, but I find writing them to be boring. That said, retesting manually is even more annoying, so I write tests. The thought that there has to be a better way, never passed. I tried a few approaches. After some experimentation, I think I have the answer - DDT (Data Driven Testing)

Before we begin

I will be converting this series into an ebook, or something like that, with additional source code and examples. If You want to get it please subscribe:

Establishing the baseline

Before we dig into what Data Driven Tests are, let’s look at some standard, non-DDT tests.

What we will be testing?

There is a fragile line for code examples. Too simple and they lose any business applicability. Too complicated and the domain overwhelms the problem described. Let me know if this problem works.

We will be testing an automatic gearbox controller for a car. This “simple” box decides when to change gear. Our version will get the following inputs:

- Gear

- Acceleration applied (values in the range of 0 to 1 in our example)

- RPM (Rotations Per Minute), so how fast the engine is turning.

The return value is only one - the gear the engine should use. It sounds simple. Let’s see some tests.

The starting point. No Data Driven Tests

public class GearCalculatorTests

{

[Test]

public void ShouldReduceGear_whenAcceleratingRapidlyOnLowRPM()

{

//Arrange

const int initialGear = 5;

const double rapidAcceleration = 0.7;

const int currentRpm = 2000;

//Act

var gear = new GearCalculator().Calculate(rapidAcceleration, currentRpm, initialGear);

//Assert

Assert.AreEqual(initialGear - 1, gear, "The gear should decrease by one");

}

[Test]

public void ShouldNotReduceGearWhenOnFirstGear_whenAcceleratingRapidlyOnLowRPM()

{

//Arrange

const int initialGear = 1;

const double rapidAcceleration = 0.7;

const int currentRpm = 2000;

//Act

var gear = new GearCalculator().Calculate(rapidAcceleration, currentRpm, initialGear);

//Assert

Assert.AreEqual(initialGear, gear, "The gear should stay the same");

}

[Test]

public void ShouldNotReduceGear_whenAcceleratingNotRapidlyOnLowRPM()

{

//Arrange

const int initialGear = 5;

const double nonRapidAcceleration = 0.4;

const int currentRpm = 2000;

//Act

var gear = new GearCalculator().Calculate(nonRapidAcceleration, currentRpm, initialGear);

//Assert

Assert.AreEqual(initialGear, gear, "The gear should stay the same");

}

}

Refactoring to Data Driven Tests

What are Data Driven Tests?

Not what we have some baseline, let’s define what a Data Driven Test is.

It might sound obvious. We don’t mix data with code. Don’t we? Look at the tests above and try to recall if your tests aren’t splashed with a big dose of setup objects. They probably are.

Some people argue saying that this is normal. Test need testing data. I am not saying they don’t. I’m saying that we should not couple test logic and test data so strongly. A few arguments to back up that statement:

- Tests should always be optimized for readability. Tests have a lot of boilerplate. Mocks, stubs, test data classes, mocked methods, etc. All this code makes it hard to know what is the boilerplate and what is the needed data. Therefore it makes the tests less readable.

- Test cases should always be optimized for readability. Again about readability? Yes, but in a different take. Let’s take two tests testing the same class, but a different path. Let’s say they are a medium size test with ~100 effective lines of code. What will be the difference between those two tests? I’m betting below ten lines of code. That is 10%. Even if the tests are readable, the difference between them is not.

The problem with tests like above is that new ones will be made by copying an old test and changing some lines (making the 10% changes). Lowering readability further on. Now let’s refactor the above tests to Data Driven Tests.

Version 0.1 Refactoring

The first step is to extract the data from the test code. Let’s put in into a function:

private void CalculateAndVerifyGear(double acceleration, int currentRpm, int gear, int expectedGear){

//Act

var calculatedGear = new GearCalculator().Calculate(acceleration, currentRpm, gear);

//Assert

Assert.AreEqual(expectedGear, calculatedGear);

}

Now, to use it:

public class GearCalculatorTests

{

[Test]

public void ShouldReduceGear_whenAcceleratingRapidlyOnLowRPM()

{

//Arrange

const int initialGear = 5;

const double rapidAcceleration = 0.7;

const int currentRpm = 2000;

CalculateAndVerifyGear(rapidAcceleration, currentRpm, initialGear, initialGear - 1);

}

[Test]

public void ShouldNotReduceGearWhenOnFirstGear_whenAcceleratingRapidlyOnLowRPM()

{

//Arrange

const int initialGear = 1;

const double rapidAcceleration = 0.7;

const int currentRpm = 2000;

CalculateAndVerifyGear(rapidAcceleration, currentRpm, initialGear, initialGear);

}

[Test]

public void ShouldNotReduceGear_whenAcceleratingNotRapidlyOnLowRPM()

{

//Arrange

const int initialGear = 5;

const double nonRapidAcceleration = 0.4;

const int currentRpm = 2000;

CalculateAndVerifyGear(nonRapidAcceleration, currentRpm, initialGear, initialGear);

}

}

The refactor has a few problems:

- We lost the assert message (it could be added to our version, but most tests have more than one assert. Passing many assert messages will make the test unreadable)

- New tests will still be made by copying an old one and changing a few dials. Changes will be more visible, but this still isn’t good enough.

- Test data still isn’t a first-class citizen.

- When looking at those tests, I get the feeling that there should be a better way.

Version 0.2 - Making test data a first-class citizen

There are a few ways the problems mentioned above can be addressed. We will go over them one by one.

From here on we will use NUnit. If You prefer XUnit or any other testing framework, check the documentation. It probably supports Data Driven Testing.

The first way is to use a TestCase attribute. It allows to pass parameters to tests. After refactoring the code will look like this:

public class GearCalculatorTests

{

[TestCase(0.7, 2000, 5, 4, Description = "When accelerating rapidly on low RPM should reduce gear ")]

[TestCase(0.7, 2000, 1, 1, Description = "When accelerating rapidly on low RPM should not reduce gear when on first gear ")]

[TestCase(0.4, 2000, 5, 5, Description = "When accelerating NOT rapidly on low RPM should not reduce gear")]

public void CalculateAndVerifyGear(double acceleration, int currentRpm, int gear, int expectedGear)

{

//Act

var calculatedGear = new GearCalculator().Calculate(acceleration, currentRpm, gear);

//Assert

Assert.AreEqual(expectedGear, calculatedGear);

}

}

Yes, that is all. Initial 45 lines of tests now take 15 lines of code and are more readable. Now I see that I could remove the current RPM from the tests data because it never changes.

This approach is better than what we started with, but has some drawbacks:

- Attributes can only have parameters that are known on compile time.

- We can’t pass complex objects to attributes.

- There are no compile-time checks for the wrong number of parameters (Resharper will show a warning).

- Values in attributes aren’t that readable.

- Having four attributes is OK, but more of them will be messy.

- It is hard to read what we are asserting.

Let’s first address the last point.

Version 0.2.5 - Better asserts

To better express what we are asserting, we can use the ExpectedResult from TestCaseAttribute. After refactoring it will look like this:

[TestCase(0.7, 2000, 5, ExpectedResult = 4, Description = "When accelerating rapidly on low RPM should reduce gear ")]

[TestCase(0.7, 2000, 1, ExpectedResult = 1, Description = "When accelerating rapidly on low RPM should not reduce gear when on first gear ")]

[TestCase(0.4, 2000, 5, ExpectedResult = 5, Description = "When accelerating NOT rapidly on low RPM should not reduce gear")]

public int CalculateAndVerifyGear(double acceleration, int currentRpm, int gear)

{

//Act

return new GearCalculator().Calculate(acceleration, currentRpm, gear);

}

How this works:

- now our test returns a value.

- this value will be compared with the value of

ExpectedResult

It is a bit better, but we still have to address drawbacks 1-4.

Version 0.3 - TestDataSourceAttribute

We can adress most of the drawbacks by using the TestDataSourceAttribute. This attribute allows defines a method that will generate test cases by creating a TestCaseData objects. Let’s see it in action and explain later:

public class GearCalculatorTests

{

public static TestCaseData[] TestDataSource

{

get

{

return new[]

{

new TestCaseData(new GearBoxTestData(0.7, 2000, 5))

{ ExpectedResult = 4, TestName = "When accelerating rapidly on low RPM should reduce gear "},

new TestCaseData(new GearBoxTestData(0.7, 2000, 1))

{ ExpectedResult = 1, TestName = "When accelerating rapidly on low RPM should not reduce gear when on first gear "},

new TestCaseData(new GearBoxTestData(0.4, 2000, 5))

{ ExpectedResult = 5, TestName = "When accelerating NOT rapidly on low RPM should not reduce gear"}

};

}

}

[TestCaseSource(nameof(TestDataSource))]

public int CalculateAndVerifyGear(GearBoxTestData data)

{

//Act

return new GearCalculator().Calculate(data.Acceleration, data.Rpm, data.Gear);

}

}

public class GearBoxTestData

{

public GearBoxTestData(double acceleration, int rpm, int gear)

{

Acceleration = acceleration;

Rpm = rpm;

Gear = gear;

}

public double Acceleration { get; set; }

public int Rpm { get; set; }

public int Gear { get; set; }

}

A few things to note:

- We could also pass parameters the same way as with

TestCase, but not using the power of dedicated class would be a waste of potential. - Notice that the method has to be

static. Why? Because this generates separate tests for eachTestCaseData.

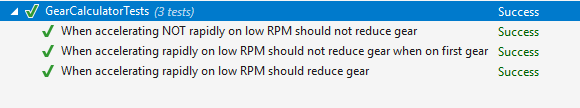

How this works is that a test runner first calls the method defined in TestCaseSourceAttribute and generates tests based on data returned. Each TestCaseData will be seen as a separate test:

Depending on the runner, each test can be debugged separately. They behave just like any other tests.

Is this the end?

No. But this post is long enough as an introduction. Following tips and tricks.