This article is Part 2 in a 4-Part Series.

- Part 1 - Refactoring to Data Driven Tests

- Part 2 - This Article

- Part 3 - Tips, tricks, and good practices for Data-Driven Testing. Part 1.

- Part 4 - Tips, tricks, and good practices for Data-Driven Testing. Part 2.

The previous post was meant to be an encouragement and a warmup to data-driven testing. This post describes why I love this way of testing. Understanding a simple fact about testing moved me from “Oh, I should write tests” to “I want it all! And I want it now!” and Data-Driven Testing. And the simple truth is:

Before we begin

I will be converting this series into an ebook, or something like that, with additional source code and examples. If You want to get it please subscribe:

Data is the king

Anyone who is a bit interested in machine learning heard statements like data is the king, data is the new oil, etc. The same applies to tests. Having tests provides very little value. Having tests with the right test data provides huge value. Let me explain. Previously I wrote that I don’t like writing tests. Writing tests is one of two:

- It is a verification of the quality of the code you produced.

- Or can be the verification of the skill in hacking using mocks, stubs, and fakes you poses.

Pick one. I will concentrate on the first option. In it, writing tests is fun and engaging. It requires a lot of rethinking of previous assumptions, has a very short feedback loop, and gives a feeling of satisfaction. Fun and awesome.

The part that drains my mental energy the most is producing test cases and test data. This part is:

- boring.

- doesn’t require significant thought.

- in most cases is copying previous data and changing one variable.

- repetitive

- doesn’t give any feeling satisfaction

All the above reasons made me try most auto testing approaches in the .net ecosystem with the biggest hopes for Pex But, like most Microsoft products, it died. And for a good reason. It approached producing testing data from the wrong angle. It analyzed the code and found edge cases. Sounds reasonable - this is how we write tests and why we write tests. To test the edge cases. But is it how we should write tests? No! Writing tests this way is just duplicating the conditions from ifs, switches, etc. We end up with tightly coupled, made-up tests.

I am not saying that such tests aren’t necessary. They are useful. But only initially, the first verification. Once we verified that the code is working, or we want to test more complex logic, they become too expensive. Time invested in them produces a minimal gain. It makes no think of the data that will cover all paths. But we need the data to test the code. How to get it?

How to get test data

Where to get better test data? That is simple - from the users. A user of our code is a developer, a tester, or a triggered job that will call it. In this case

All we need to do is to log the call data. This functionality can be already implemented or might require some tinkering in our app. Let’s examine a few usages.

Messages

Some architectures are better than others for gathering data for data-driven tests. Message-based ones are near perfect. Most message systems have the notion of a dead letter queue - a queue that contains messages that failed to process (thrown an exception). The dead letter queue makes for a perfect input to our data-driven tests. If we want to have a better correlation of the message and the exception or wish to have all the data in logs, we might do something like this:

public class MyHandler<MyMessage>{

/*

initization code etc...

*/

public async Task Handle(MyMessage m){

try{

// message handling logic here

}catch(Exception ex){

var messageJson = JsonConverter.SerializeObject(m);//the call failed, but we have access to the message that coused the error.

_logger.LogFailedMessages(messageJson,ex);

throw ex;//we need to throw to mark the message as failed so it is retries or put into dead letter queue.

}

}

}

The above is a very simplified implementation designed to show the idea, so please don’t use it on production. A better way to implement it is to hook this code in the code calling the handlers.

Asynchronous processing

A simplified bit easier to implement approach is to use async processing. I don’t mean the use of async keywords in controllers, but splitting the business process into asynchronous jobs that can be processed later.

Example: We register the user, but create a job that will send the confirmation email.

For this I use Hangfire.

A shameless plug: I wrote a series of articles on Hangfire and how it works.

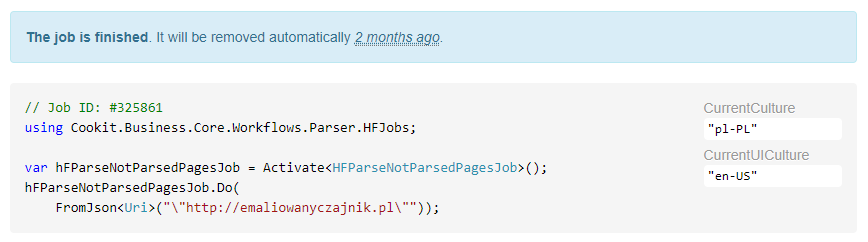

It makes it even simpler than messaging. Hangfire displays execution parameters with the thrown error in the Hangfire dashboard:

MVC/WebApi

Http calls make it more tricky, but still possible. The same try/catch logic can be implemented in the controller methods directly, but a more general solution is to have a global filter. Something like this:

public class MyErrorFilter : IActionFilter

{

public void OnActionExecuted(ActionExecutedContext context)

{

if ( context.Exception != null && !context.ExceptionHandled) {

// get data from context.HttpContext.Request

}

}

}

The code above is not for production use. Especially since HTTP calls logging requires considering a few additional things:

- You have to filter our typical HTTP errors (404, 400, etc.)

- If the website is public, you will get a ton of automated scans looking for

/phpadminand some injection attempts. Those have to be filtered out. - HTTP requests, more often than the previous, contain sensitive data such as user and password, cookie values, etc. Don’t log those. Never.

Logging on this controller level has one significant disadvantage when compared to the previous options. Unit and data-driven testing for controllers is hard. How to do it better?

Log on business methods level

The more pinpointed the logging, the better. Ideally, every vital method that has a data-driven test should be logging call data. Here, we might encounter the banana problem.

Trying to serialize HTTPContext, DBContext or anything with lazy loading might result in us trying to serialize the whole application world. Not passing such objects is a good codding practice. Simple and narrowed down classes are better anyway.

Things to consider when logging input parameters for data-driven tests:

- Sensitive data. Logs are very often treated with not the same care as the database. Adding input data logging means that they should be. They will contain important data.

- GDPR. Adding such logging, we are adding yet another place to monitor for user data.

- Data size. It is very easy to create tens of thousands of such logs. Filter them out and fix fast.

- Not a silver bullet. This approach requires architecture changes. Just dropping it into an application with global state won’t provide to much value.

- Performance. We are logging only in case of a failure. Why care about response timings so much? The user won’t be happy anyways. What if the user is not human and we are getting thousands of such errors a second? Logging is making our situation just worse. Be careful, notify Your Ops team.

- Just logging is not enough. Only logging won’t make your system better. Logging is so that it is easier to fix the bugs. Don’t forget about that.

Creating data-driven tests

I have the data now what?

- Format it. Remember, tests should be optimized for readability.

- Save it to a special directory

- Read it and use it in a test.

Remember the TestCaseSourceAttribute from the previous article? Just change it into something like this:

public static TestCaseData[] GetData()

{

var retArray= Directory.GetDirectories("MyTestDataFolder", "*", SearchOption.AllDirectories)

.OrderBy(a => a)

.Select(a =>

{

var ret = new TestCaseData(JsonConverter.DeserializeObject("testdata.json"));

ret.ExpectedResult = JsonConverter.DeserializeObject("expectedResult.json");

ret.SetName(a.FolderName);

return ret;

})

.ToArray();

return retArray;

}

Some assumption:

- Each test is in a separate folder.

- The name of the folder describes the test case.

- Each folder has a

testdata.jsonfile containing the test data object. - Each folder has an

expectedResult.jsonfile containing the expected result object.

I started with the intention to write a tips and tricks entry, but after a few conversations, I saw that a part about gathering data is missing. I promise tips, tricks and good practices are next! If you don’t want to miss it, subscribe to the newsletter.